Educational Inequality From the Eyes of Data

One of the most fundamental disparities between rural and affluent urban schools lies in education funding. According to the U.S. Department of Education, roughly 45% of school funding nationwide comes from local property taxes, meaning areas with higher property values like the Bay Area can invest significantly more per student. For instance, California’s wealthy suburban districts spend up to $20,000 per student annually, while many rural Kentucky or Mississippi districts spend under $10,000. This funding gap translates into outdated textbooks, fewer elective courses, and limited access to modern technology. Wealthier schools often boast advanced STEM labs, performing arts centers, and small class sizes; rural schools may struggle to maintain basic infrastructure, let alone support enrichment programs.

Beyond funding, rural students often have less access to Advanced Placement courses, dual-enrollment programs, and specialized electives that strengthen college readiness. Data from the National Center for Education Statistics shows that only 50% of rural high schools offer any AP courses, compared to 90% in suburban areas. Similarly, rural schools frequently lack extracurricular programs like robotics clubs, debate teams, or research internships that are standard in well-resourced districts. These activities are crucial for developing leadership, critical thinking, and teamwork—skills that affluent students often showcase on college applications.

Teacher shortages disproportionately impact rural schools. The Learning Policy Institute reports that rural districts experience 50% higher teacher turnover than urban ones, largely due to lower pay and professional isolation. Many rural schools lack subject-specific teachers entirely, especially in STEM fields. Students may learn physics from a teacher without a physics degree or attend schools where foreign languages are not offered at all. Meanwhile, affluent schools in areas like the Bay can recruit experienced educators with strong academic backgrounds, offering salaries 20–30% higher on average.

Counselor access is another issue. The American School Counselor Association recommends one counselor per 250 students, yet rural schools average one per 400–500 students. This limits personalized college guidance, especially when navigating complex application systems or financial aid. Bay Area schools, conversely, may provide dedicated college advising teams or external partnerships with universities, giving their students a major advantage in pursuing selective institutions.

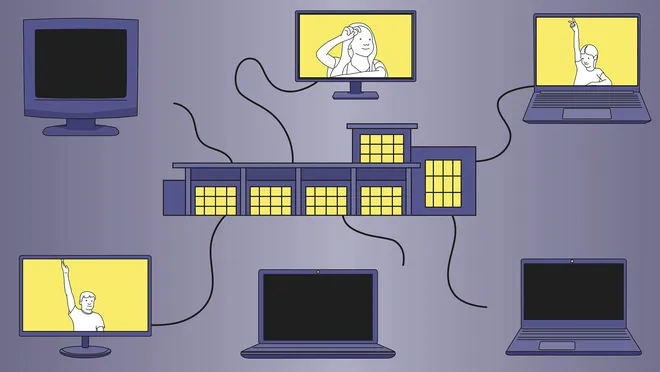

In today’s world, technology is inseparable from learning. However, reliable access remains a challenge for rural students. The FCC reports that over 22% of rural Americans lack broadband internet, compared to just 1.5% in urban areas. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this divide became starkly visible: many rural students relied on mobile hotspots or even parking lot Wi-Fi to complete assignments, while Bay Area students participated in virtual coding bootcamps or interactive STEM simulations.

All these factors converge in postsecondary outcomes. According to the National Student Clearinghouse, only 59% of rural students enroll in college after high school, compared to 67% of suburban students and 74% of those in affluent metropolitan areas. Among those who do enroll, rural students are less likely to attend four-year institutions and more likely to drop out before graduation. A lack of exposure to diverse careers, coupled with limited mentorship and financial aid literacy, contributes to this trend.

In contrast, students from the Bay Area benefit from a rich ecosystem of mentorship, internships, and nearby universities—Stanford, Berkeley, and San José State among them—offering both access and inspiration. The result is a persistent opportunity gap: while rural students may possess equal potential, they operate within an ecosystem that offers fewer tools, connections, and pathways to success. Without targeted interventions in infrastructure, teacher recruitment, and digital access, the rural-urban divide in educational opportunity will only widen.